Home Mail Articles Supplements Subscriptions Radio

The following article appeared in Left Business Observer #127, June 2010. Copyright 2010, Left Business Observer.

Like this? Subscribe today! There’s a lot more where this comes from—and only some of it makes it to the web for free consumption.

Old world, new crisis

A bit of horn-tooting to start. In a 1998 article on the imminent creation of the euro, LBO noted several intensely serious problems with the project. In the economic realm, the architects of monetary union seemed not to have appreciated the risk of yoking together countries as disparate as Portugal and Spain with France and Germany; the first pair had average incomes about half that of the second pair, with technology gaps to match, into a single currency zone. And in the political realm, there was the problem of a lack of any common politics—each country had its own fiscal policy, there was no common foreign policy, internal labor mobility was modest, citizens voted mainly in national rather than continental elections, and there was little popular support for or even understanding of the whole project of economic unification. The outcome could be, as the article said, “financial chaos.” We are now living through that chaos.

It did take some time to get here. But nothing like a once-in-2.5 generations global economic crisis to reveal the fissures underlying what from a distance seemed like a relatively placid surface. At first, Europe looked immune to that crisis. In fact, a new book, Europe’s Promise, by Steven Hill, touted the continent as a model of a more stable, humane model for a USA looking to emerge from the disaster it plunged the world into. Since books are slow-cooked things, Hill’s volume had nothing to say about Europe’s version of that crisis—or the austere regimen that the Euro-elite prescribed for its troubled periphery. Next to nothing about Iceland, Latvia, or the so-called PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain)—or about German sadomonetarism.

Tensions

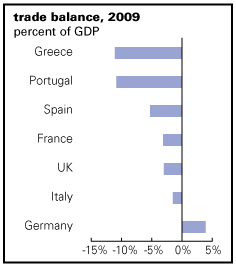

But under that placid surface, huge imbalances were developing—and not just within the eurozone, the sixteen countries that use the euro. For example, most of the peripheral countries entered the crisis years with huge net foreign liabilities. According to the OECD, as of 2007, the last boom year, Iceland’s international investment position—the difference between debt owed by Icelanders to foreigners and that owed by foreigners to Icelanders, plus foreign stock and corporations held by Icelanders less Icelandic stock and corporations held by foreigners—was –105% of GDP, the deepest hole of all the richer countries. Greece was a close second, at –94%. Portugal (–90%) and Spain (–70%) weren’t far behind. By contrast, the U.S., normally seen as a profligate, looks modest at a mere –18%. (Of course, the size of the U.S. means that its 18% matters for the whole world, while Iceland’s 105% mattered mostly for Icelanders.) Italy was in only a shallow hole at –5%—but core countries like France (+13%) and Germany (+27%) were solidly in the creditor camp. During the fat years, the debts didn’t seem to matter—actually, they magnified the boom. But there’s nothing like a recession to turn a potential problem into an actual one.

Among the first crisis victims were Iceland and Latvia, both outside the eurozone (but with massive debts, mostly in euros). Both were governed my enthusiastic neoliberal regimes that deregulated finance with enthusiasm and experimented recklessly with leverage. As often happens in these circumstances, the foreign accounts got grossly out of whack. Iceland’s current account deficit—the balance on trade in goods, services, and investment income, a broader concept than the more familiar trade balance—hit a whopping –40% of GDP in 2008, the most deeply negative number for a rich country in the IMF’s database. Latvia’s –23% in 2006 looks modest only next to Iceland’s mega-number. Current account deficits like that can only be financed with huge amounts of foreign borrowing—which can generate nice booms while they’re going on. But they always end in terrible crashes. Worse for Icelanders and Latvians, almost all of that borrowing was denominated in foreign currencies, since their own native units had no international standing. Latvia’s currency, the lats, didn’t crash when the bubble burst—its value is tied to the euro—but Iceland’s did, losing 70% of its value against the euro, meaning that its debt burden more than tripled from a domestic perspective.

Latvia’s fixed exchange rate has worsened its problems, by killing exports. The country’s GDP is off about 25%, on par with what the U.S. experienced between 1929 and 1933. Real wages are down by 11%, and unemployment is approaching 20%. Iceland’s economy, with a flexible exchange rate, has contracted about half that much.

Within the zone

So much for the problems outside the eurozone. The problems within the zone are a somewhat different ball of wax. Most of the eurozone countries in trouble have big foreign debts and lagging productivity—but they’re denied the outlet of a devaluation. And there are some particular problems with the euro project itself.

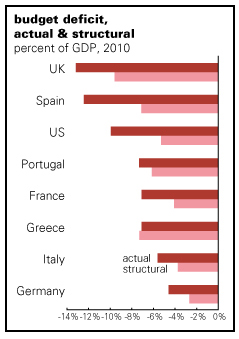

Each of the troubled countries on the Europeriphery has its own story. Greece’s government borrowed heavily, lying (with the help of Wall Street) about just how much it was borrowing. The private sector, businesses and households, is in much better shape. Italy’s government has big debts, but they’re mostly owed to Italians; Italians don’t like to pay taxes, so they save the money and lend it to their government instead. Spain had an enormous housing boom; most of its foreign borrowing was by businesses and households, not the government.

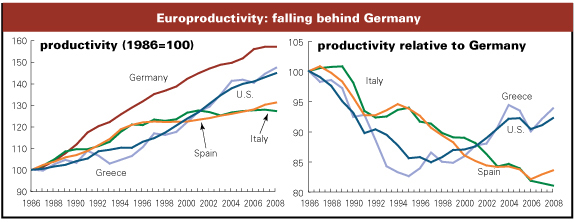

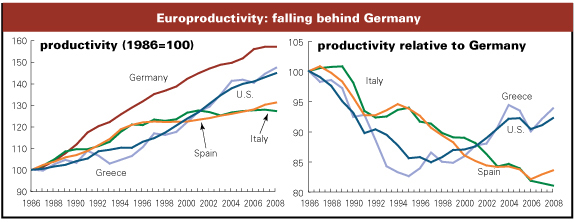

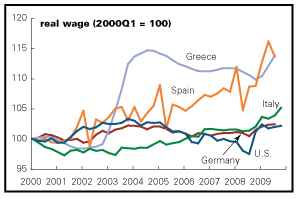

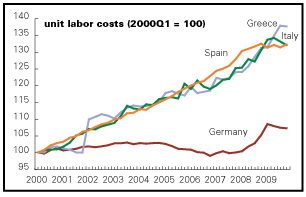

But, financial details aside, there’s also a fundamental economic problem on the Continent. As noted at the beginning of this piece, there’s a wide disparity in incomes and productivity among the members of the eurozone. Average Greek, Italian, and Spanish incomes (measured by per capita GDP) were 10–15% below Germany’s in recent years. Portugal was even further behind, about 35% below Germany. Underlying those gaps are big differentials in labor productivity—how much workers can produce in an hour of toil. If the peripheral countries were catching up with German productivity, tensions within the eurozone would be ebbing. But Germany is pulling further ahead of most of them. And it’s not just productivity. Germany has kept a lid on real wages, meaning that pay levels are lagging productivity growth. As a result, German unit labor costs—how much workers have to be paid to produce a unit of output, which is a function both of productivity and pay—are falling. That of the peripheral countries is mostly rising. Or, to put it in word rather than numbers: there are few Mediterranean names that can rival Mercedes, SAP, or Siemens.

In the old days, meaning before the euro, countries under such competitive pressures could have devalued their currencies. Devaluations aren’t painless—they raise the cost of imports and add to domestic inflationary pressures. Nor are they signs of economic vigor. Over the very long term, as Anwar Shaikh and a legion of his graduate students working on individual country studies have shown, relative currency values are determined by relative productivity performance. That is, countries with productivity growth exceeding that of their trading partners tend to see the value of their currencies rise; productivity laggards tend to see declining currencies. And over the long term, that means that the laggards are getting poorer relative to the leaders. It’s hard to find a historical example of a country devaluing its way to prosperity. Still, a devaluation can take the short-term pressure off—soften the effects of a currency crisis, stimulate exports, and reduce tendencies towards an austerity program as a “solution” to the problem. That outlet is now denied to Greece et al.

Resolutions

Instead, the Euro-elite, with Germany in the lead, is promoting a kind of devaluation through austerity: wages in the peripheral countries must be slashed, the assembly line speeded up, and fiscal policy massively tightened, meaning taxes raised and benefits cut. This is a conscious policy, not an accidental byproduct. The Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis reports a recent conversation with an officer of the European Central Bank, a German national, who cheered on the wage cutting in the periphery, noting that there was no risk of blowback to Germany. Since Germany exports high-end products like BMWs to global elites, who are presumably either unscathed or even enriched by austerity programs, the fate of mass purchasing power on the periphery bothers the anal retentives of Frankfurt not at all.

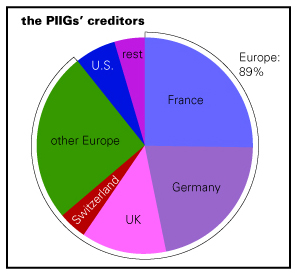

Though the psychology of austerity is far from unimportant, Germany and its other core colleagues have a deep material interest in squeezing the periphery. As the graph on p. 7 shows, most of the PIIGS’ debts are owed to banks in the European core. (The picture would be nearly identical for Iceland and Latvia.) The last place that creditors look to squeeze for cash is to their BMW-driving class colleagues abroad. And from the core’s point of view, if you squeeze wages and benefits hard, labor gets a lot cheaper and more desperate, making the prostrate debtors better investment targets.

There’s a softer way to go about the adjustment. Greece and other troubled countries could have their debt refinanced by the creditors at lower interest rates and longer maturities. More radically, the bondholders could take a hit, getting paid maybe 80 cents on the euro instead of 100. Needless to say, these are not live options at the moment. Neither is the quasi-revolutionary fantasy of repudiating the debt and leaving the eurozone. Instead, Greece is likely to get some help rolling over its debts from the EU and IMF, but not without an enormous dose of austerity. That’s nastier than Washington’s response has been to our economic crisis—at least until Obama’s deficit commission unveils our own austerity program.

Can the euro survive this crisis? Not only has this melodrama exposed the contradictions in the economic model, it's also shown the political immaturity of the EU's institutions. Though there is a European Central Bank, handling a Greek rescue is the business of sixteen finance ministries and national parliaments—some of them representing creditor countries, and some, debtors. And what if the crisis spreads to Spain, a country with three times Greece’s foreign debts? Might it make bourgeois sense to show the peripheral countries the exit and leave the euro to Germany, France, the Netherlands, and a few others—maybe Italy, if it behaves? Can that be done in an orderly way, or would it provoke further financial panics?

Oh, and so much for the idea that the euro would replace the dollar as the central global currency.

Home Mail Articles Stats/current Supplements Subscriptions Radio