Home Mail Articles Supplements Subscriptions Radio

The following article is a draft of one that will appear in Left Business Observer #116, forthcoming later in August 2007. It retains its copyright and may not be reprinted or redistributed in any form - print, electronic, facsimile, anything - without the permission of LBO.

Reflections on the current crisis

Quite a few weeks the financial markets have had. What’s it all mean?

The Internet left is getting all heated up—this is the Big One, the End of the World, the Death Agony of Capitalism. Maybe; that’s always possible. But it’s not likely.

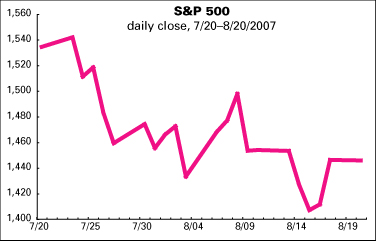

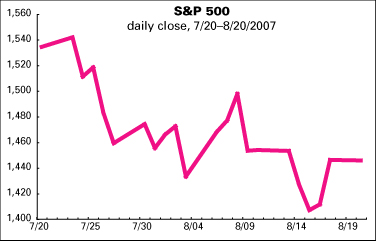

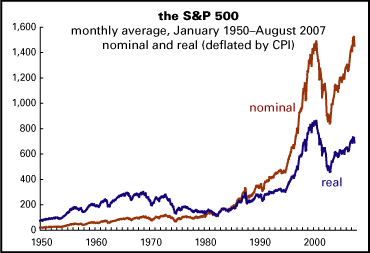

And measured by the stock market, as the graphs show, the crisis looks big in the short term...

...but virtually disappears in the long (as does the 1987s stock market crash).

A technical analyst of the stock market might look at the long-term chart and see a weak new high in nominal terms and a failure to match an old high in real terms, something that if confirmed, might be something to worry about.

Roster of crises

We’ve been here, or something like here, several times over the last 25 years. There was the financial rout of the early 1980s, inspired by Paul Volcker’s highly successful strategy of killing 1970s inflation by strangling working class power. It culminated in Mexico announcing that it could no longer service its foreign debts, the moment of onset of the Third World debt crisis of the 1980s. There were repeated worries it would bring down the whole global financial system. Some banks took some earnings hits, but capital—personified by the U.S. Treasury and the IMF—turned the crisis to its advantage, by beginning the long process of structural adjustment and market opening that gave us the neoliberal world we live in today. And at home, the U.S. working class, terrified by an unemployment rate that peaked at 10.8% at the depths of the recession in late 1982, renounced all traces of the militancy and surliness of the late 1970s.

Later in the decade, there was the 1987 stock market crash, which occurred just after LBO’s first birthday. Young and naïve, the newsletter delivered prophecies of gloom that never materialized. (For more on all this, see the 20th anniversary thumbsucker.) Then the leveraged buyout mania collapsed, and the savings and loans, which had spent much of the decade in a death spiral, finally crashed. The consequence? Thanks to a $200 billion federal bailout and a policy of sustained low interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve, there was no depression. There were several years of slow growth in incomes and employment, but the unemployment rate peaked at 7.5%, well below 1982’s level (not to mention 1933’s 24.9%).

It took a few years for the U.S. economy to recover from the debt hangover of the 1980s, but by 1994 things were cooking once again. By midyear, employment was growing at a 3.5% annual rate, twice the current speed—causing the Fed to push up interest rates in order to slow things down. (You can’t have labor markets get too tight, or there might be a relapse of that 1970s militancy and surliness.) By yearend, the rise in interest rates squeezed Mexico, helping to push the country into a financial crisis and sharp recession. The usual gang—the U.S. Treasury, the IMF, and the rest—launched a bailout (on which the U.S. Treasury actually made money), that prevented a localized financial crisis from spreading globally. The bailout did not spare Mexico from severe recession, but it did prevent generalized collapse, which was exactly the intention of its designers.

Later in the decade there was the Asian crisis of 1997-1998. Once again, intervention by the authorities prevented a generalized financial meltdown, though it did not spare countries like Thailand and South Korea from deep recession.

And, a few years later, back at home, the whole dot.com mania blew up, bringing the boom of the 1990s to an end, and revealing a host of corporate scandals. Once again there were prophecies of doom, and also proclamations that the scandals would prompt the masses to wake up and throw off the corporate yoke. Though millions saw their retirement savings clipped, or even totally wiped out, there was neither a generalized collapse or a popular rebellion.

Roots of drama

Enough history. What’s going on now?

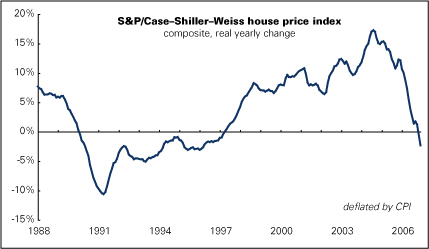

The root of the present drama is in the huge housing mania—and the financial adventurism that surrounded it—that took hold of the U.S. in the mid-1990s and accelerated after the stock market collapsed in 2000–1. (For background, see this prescient 2005 LBO article.) Several aspects of the bubble have left behind a toxic residue.

Most obviously, people stretched to buy houses they couldn’t afford, and now find themselves “embarrassed,” to use the quaint 19th century term for being unable to service one’s debts. Lenders went absolutely mad, pushing mortgages out the door, often with little regard about whether the borrowers could pay. And borrowers took on mortgages that were beyond their means, either because their bankers lied to them about the terms (or, it must be conceded, they lied to their bankers about their means, and the bankers weren’t asking many questions) or because they’d hoped that house prices would continue to rise and make today’s stretch look like next year’s bargain. In many parts of the country, a bungalow runs half a million dollars, which means not much of a choice on price if you’ve got to buy. Given the American fetish for homeownership, many people don’t even consider a rental, even though it can cost half as much as a purchase.

As the boom progressed, bankers got more creative, pushing “teaser” mortgages with low initial payments for the first two or three years that would eventually adjust to levels that were 50–100% higher for the remaining 27 or 28 years of the loan. These terms weren’t always fully disclosed—but even when they were, many borrowers hoped that something would turn up to make things work out. But they’re resetting now, and payments that were once manageable are now becoming unmanageable. And as the chart shows, the long runup in house prices has gone in to reverse.

The onset of crisis

The problems began in the subprime sector—loans made to low-income borrowers, or people with spotty credit histories—as 2006 was turning into 2007. As the months progressed, it became clear that things were getting considerably worse. Wall Street, which had initially shrugged its shoulders at the problem, grew more alarmed—appropriately enough, given its role in stoking the mania (more on that in a bit).

If the problem remains confined to the subprime sector, and only a small minority of that, then things shouldn’t get too out of hand. (That’s at the systemic level; for people who are on the verge of losing their houses, their worlds are falling apart.) Subprime loans make up about 15% of the mortgage market, and their cousins, so-called Alt-A’s, which occupy an intermediate realm between subprime and prime, another 12%. Not all these loans are going to go bad—not close to that. But 10–15% of these are judged to be at high risk of default (e.g., they were for no-money-down deals, or “lim doc,” industry jargon for limited documentation, which means the lender didn’t ask for proof of income). Of course that assumes that the economy doesn’t go into the tank; if that happens, a lot of loans that look prime now will turn sour as well.

But the distress in the mortgage business is highly unusual for a period when the economy is in relatively decent shape. According to the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), foreclosures were started on 0.58% of outstanding mortgages in the first quarter of 2007 (we’ll get second quarter figures in September). That may not sound like much, but it’s the highest on record, surpassing the previous 0.50% high set in 2002, when the job market hadn’t yet recovered from the recession. (It’d be nice to graph all these numbers, but the MBA doesn’t allow it.) This is largely being driven by the subprime problem. The overall delinquency rate, at 4.84% isn’t high by historical standards, but those seriously behind on their bills—60 to 90 days—are 1.91% of those outstanding, very close to a record, surpassed only by 1986’s 1.98%. But in 1986, the unemployment rate was around 7%, vs. 4.6% now, and the average interest rate on a new mortgage was around 10%, vs. 6.7% now.

If the unemployment rate continues to drift higher—and all indications are that the Federal Reserve would like it to—then the delinquencies will certainly rise, especially as the teaser mortgage payments reset higher. And if house prices continue to decline, as seems likely, then a lot of people who’d hoped that they could sell or refinance are going to find themselves owing more than the dwelling is worth.

Toxic structures

The affordability issue is one side of the housing problem; the other is the financial fallout. And that’s not just a simple matter of the lenders taking hits on delinquent mortgages. Financial life these days creates connections in the most unexpected places.

Long gone are the days when bankers kept loans on their books until the day they were paid off. Now they’re quickly packaged into bonds and sold to investors like pension funds and mutual funds. Mortgages dominate this business, but credit card debt, auto loans, student debt, and business borrowings are subject to similar treatment. Over the last decade, the market for what are called federally related mortgage pools—bonds assembled from mortgages and issued by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae—has more than doubled; that for other asset-backed securities (like credit card debt, etc.), as more than quintupled. Over the last two decades, they’ve gone up sevenfold and forty-six-fold respectively. These are truly enormous numbers, even by the standards of the U.S. financial markets.

There are at least three consequences of the “securitization” of individual loans. One is that lenders have little incentive to worry about the creditworthiness of their borrowers; who cares, if you’re just passing the debt out the back door a couple of minutes after it came through the front door? Second is that problem loans can end up widely distributed throughout the financial system. In placid times, that’s not really a problem; shocks can be widely distributed, reducing their impact on individual institutions. But in turbulent times, problems can be distributed around the world—thus we’ve seen several European banks and hedge funds blow up because of problems in the U.S. mortgage market. And third is that it’s a lot harder to work out problems when they arise. In the old days, if borrowers got in trouble, they could work things out with their bankers. (Emphasis on could, of course.) Now, a lot of debtors don’t even know to whom they owe money.

And it’s gotten so that even this sort of securitization seems innocent. In recent years, Wall Street’s finest minds have packaged mortgages and other debts into complex exotic securities—things with names like collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). This isn’t the place to explain exactly what those are; suffice it to say that a lot of supposedly sophisticated investors who’ve bought these beauties don’t even know what’s in them. They just came with a promise to pay that now seems like a lie. Though they often bore AAA ratings, there were undisclosed subprime toxins contained within. Money market funds, which are supposed to be safe, may be among the victims. And like many of those victims, the money managers should have known better, but didn’t know, didn’t care, didn’t understand, or were lied to. Kind of like subprime borrowers.

One of the many problems with CDOs and the like is that they’re built by mathematicians who assume that the markets will always behave “normally.” That is, prices will move smoothly and that the relationships between the prices of different kinds of securities (safe vs. risky ones, say) will behave predictably. But when the financial markets experience a seizure, these conditions are violated; prices gyrate and normal relationships get stretched way out of whack. This is exactly the sort of thing that did in Long Term Capital Management back in 1998. We have that again with the mortgage market, but on a much grander scale.

Anxiogenesis

Although the subprime market is only a small share of the total mortgage market, and although subprime loans in default are only a small share of the subprime universe, the rising default rate on these loans has created a seemingly disproportionate amount of anxiety. Part of the reason for this is that, thanks to securitization and the mysterious ways of CDOs no one really knows who holds what or how dangerous supposedly safe securities will turn out to be. It may take time for all that to make itself clear. And if the underlying problem—borrowers’ inability to make their mortgage payments—gets worse, than the fear and uncertainty will also get worse.

But that’s not all. Wall Street has been very casual about risk in recent years. Repealing much of financial history, the gap between interest rates on junk bonds and other risky instruments has been only slightly higher than that on riskless assets like Treasury bonds. Investors poured money into buyout funds, hedge funds, and anything else that promised high returns without much consideration of the possibility of loss. The subprime mania could be read as a subset of that complacency. The subprime crisis can be read as the end of that complacency.

So, to use the jargon of the trade, there’s been a “repricing of risk,” and in a rather short period of time. While only a little while ago, plenty of cash was available for risky ventures, now investors want nothing to do with anything that isn’t a sure thing. So now even lenders who specialize in prime mortgages extended to the very well off are finding it hard to raise money. It’s looking like a generalized credit crunch—a period when it’s nearly impossible to borrow at any interest rate—is underway. If ordinary businesses can’t borrow to buy supplies or equipment, the real economy could be in serious trouble.

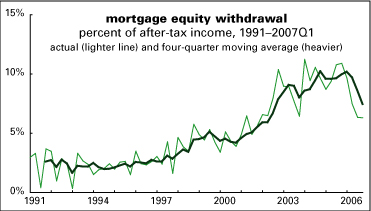

And the continuing, and probably deepening, loss of housing’s contribution to consumption and investment could be a serious drag on the real economy. About 13% of the growth in GDP from 2002 through 2005 can be traced to housebuilding. About a third of the growth in consumption over the same period came from money borrowed against home equity and spent. Almost all the home improvement expenditures came from such equity withdrawals. (The consumption and home improvement stats, and the data behind the chart below, come from James Kennedy of the Fed, in unofficial estimates that are an extension of the 2005 paper he co-wrote with Alan Greenspan.) As all these have slowed, so too has the economy. There’s also no doubt that people saved less and spent more because they thought their houses were making them richer. They don’t think that anymore. And that was before the financial markets seized up.

Anxiolysis

And this is the point where the trauma team steps in. Over the last couple of weeks, the world’s central banks have pumped cash and reassurance into the markets to keep things from getting out of control. In the lead was the usually hawkish European Central Bank; bringing up the rear was our normally indulgent Federal Reserve.

While the central bankers accomplished their immediate goal—bringing the short-term interest rates under their most direct control back to their targets, after trading way above them—they haven’t yet re-established confidence in the markets.

What’s behind the reticence of our Fed? Markets used to be comforted by the “Greenspan put”—a mythical insurance policy that the former Fed chair had granted the markets, guaranteeing them against disastrous declines, which may not have existed, and may not be possible to deliver on. But the perception that it did exist tranquilized money managers’ sense of risk. It may be that Bernanke wants to prove his toughness by putting a scare into the hearts of speculators, without putting the real economy at risk. That is, they want a manageable local crisis, not a scary systemic one. Were it making policy on real-world indicators only, the Fed would probably be in no hurry to lower interest rates; it likes the way the unemployment is rising and growth has slowed. It is worried that productivity is slipping and probably thinks that the economy needs some discipline. The desire to keep pressure on in the real world while trying to contain financial tremors probably explains their unusual move on August 17 of lowering the discount rate (the rate at which banks in trouble borrow directly from the Fed) rather than the fed funds rate, the short-term rate under its direct control that sets the tone for the credit markets.

It’s a risky game for the Fed; maybe it’s been itself tranquilized towards risk because of its long string of successes at containing crises. It may be hard to time this game so carefully. It’s annoying how Wall Street complains about protectionism protecting the incompetent and welfare corrupting the poor and then quickly turns to the state screaming for a bailout. But without a bailout—or the somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment, to quote Keynes—they could take us all down with them.

This article will be updated and expanded in LBO #115, now in preparation, and this 2005 housing article will be updated. And the issue’s Money page will report on what the Fed and its siblings are up to.

Home Mail Articles Stats/current Supplements Subscriptions Radio